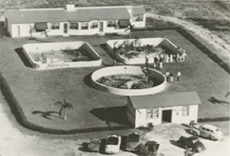

The Miami Serpentarium's beginnings were humble, started with the hard work of Bill and his son by clearing the land of the pine trees and palmetto brush to make way for some small buildings and a few outside exhibit areas. By this time Bill and his first wife had divorced, and he soon remarried, they had two daughters. His second wife had a great penchant for communicating with people, and between his efforts to build his venom production center, and her outstanding ability to convey the purpose for all the Serpentarium and Bill Haast stood for, tourists came to see this unique exhibit which was certainly a curiosity to passers by driving on U.S. 1.

At first times were lean, and reliance on beans for dinner was not an uncommon occurrence in those days, and although visitors were directed to a certain area to pay their meager entrance fee, it was not unusual to find them simply stepping over the "wall" consisting of a low shrubbery fence, and it became evident that one of the first things that needed to be added as soon as money would allow, was a real perimeter wall on the fledgling tourist attraction and venom production center.

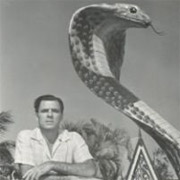

The physical structure of the Miami Serpentarium was transformed very interestingly several times, and Bill designed and with the assistance of sculptors and artists, constructed (a few times, the first was destroyed by a hurricane) a 35 foot concrete replica of a cobra looming large on the front lawn or the last and most elegant version, protruding magnificently through the flat-roof at the entrance, gazing down over the traffic on South Dixie Highway. An eye catcher for sure, it was a true work of art and a reminder to anyone in need of a sobriety check while driving for the first time down U.S. 1 after dark, that it was time to cut back on the sauce.

With the basic buildings and exhibits in place and after a few years of expansion, Bill proceeded to begin importing snakes in large numbers; mambas, puff adders, gaboon vipers and spitting cobras from Africa, asps from Europe, king cobras from Asia, fer-de-lance and bushmasters from South America. And of course, the indigenous rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths, coral snakes, and gila monsters and their southern cousins the beaded lizards of Mexico (the only venomous lizards of the world) from North America were easily accessible. It was possible and economical to import them in great numbers, because professional animal traders on each continent relied upon the native local people to bring them in for a small fee and had primarily zoos and specialty exhibits or other animal traders as customers. Of course it was then and still is today, that snakes were considered a source of food, but that is another subject entirely. Upon arrival at the Serpentarium, it wasn't uncommon to open a snake bag in which the snakes were placed before being transported in a wooden box, and find a few snakes with short knotted necklaces made from reed grass. It was easy to envision a native of India with his rudimentary snake-catching reed grass with a loop on the end sneaking up and snaring his reptile, looking forward to turning in his find in exchange for a small sum.

But a worse experience was to be endured by some animals, especially in India where the fine art of snake charming* originated over two thousand years ago and is still practiced today, but is rapidly on the decline. In order for the charmers to live long and healthy lives, it was their custom to sew the mouth of the snake shut, or they had a masterful way of cutting the fangs out at the base rendering the snake harmless. While a harsh thing to do, Bill was amazed at how clean the snakes mouth was, as if it had been done by a skilled surgeon, with no infection present. These practices were done primarily for the snake charmer's safety, but also because of the realities that snakes kept for such purpose would not eat in captivity, so their destiny was sealed at the time they were captured. They were so abundant it was simply easier to use the snakes until they could no longer perform, go out and catch more and repeat the process. Basically, because the numbers of venomous snakes were great especially in more tropical regions of the world, and as they were responsible for many snakebite deaths annually, their capture and disposal was considered a safety issue, and for whatever use they ultimately were put to, with a lot of people willing to catch them snake supply was abundant. Fortunately, due to the worldwide efforts at conservation and education, wild animals now are more protected than ever before, and hopefully such protections will continue to increase.

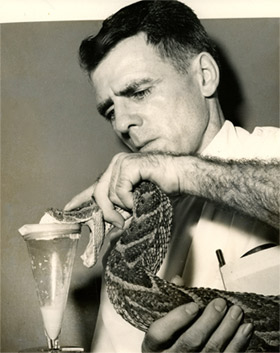

Besides insisting from the suppliers that the snakes they provided be freshly caught and have their fangs intact, (the threads from the sewing could easily be removed, as well as the reed "necklaces"), there was one other important prerequisite, and that was to be certain that the snakes were not rejects from venom producers, where the unfortunate animals after having been "milked", a process by which harsh manual pressure was applied to the delicate venom glands located on the sides of the snakes' head, causing irreparable damage to the glands, could no longer produce any quantity or quality of venom ever again, and were sometimes recycled to the animal trade.

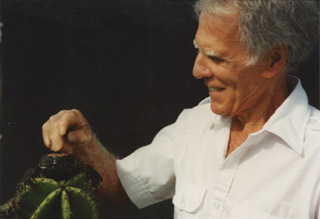

Venom collection from an African puff adder

Photo by Bob Anderson

Bill was insistent that his method of venom collection not be compared or referred to this harsh practice of "milking", but to be known as venom collection, or venom production, but in reality it was the snake doing the producing, he was simply carrying out the collection. It was a semantical difference but an important one as his method was conducted with the purpose to be as gentle with the snake as possible, give it something to bite into voluntarily, find a way to give it nourishment in spite of it's reluctance to eat, and to provide it with as humane an existence as he could under the circumstances. This enabled him to keep snakes alive sometimes for many years, and allowed him to collect more high quality venom over time from each animal than he could ever get by "milking", which ethically he would not do, although gentle massage was sometime indicated for a few truly recalcitrant individuals.

Postcard to Bill from Henry Field of the Chicago Field Museum

* Snake charming is the fine art of illusion whereby a cobra is placed in a dark basket, and the "fakir" or snake charmer sits or positions himself in front of the basket, playing a flute. Then the lid is removed from the basket, the snake becomes alarmed and rises to spread it's hood (the expansion of elongated ribs along the spine) to defend itself from the closest moving object of the swaying flute in front of him. This gives the illusion of the snake reacting and moving side to side in response to the music, being "charmed" as it were, when in fact snakes have no ears and do not hear sound in the normal decibel range of a snake charmer's flute, but do feel the vibrations of loud sounds in the base ranges.

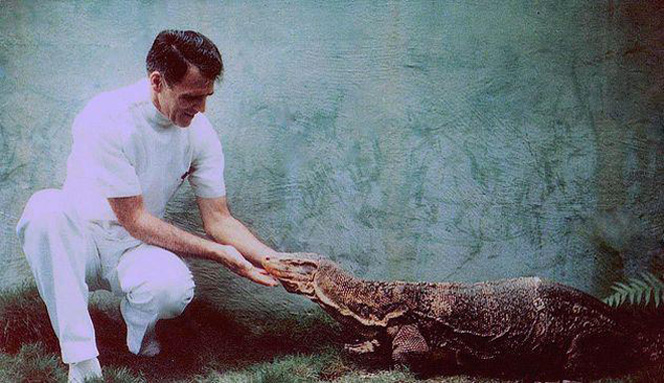

Bill with Kumo, an Asian Water Monitor obtained from Paul Allen, Jr.

Stroking a gila monster during PBS Nature program filming

Bill had great affection for all animals, and while he did not consider snakes as "pets", and snakes certainly have no need of emotional interaction with people, it caused him great personal distress to deny so many animals their freedom, but the overriding importance of the need for their venoms kept that emotion at bay; however, it was always in the background and a subconscious source of consternation for such a man with great conscience and was something to be endured. In his later years it became difficult for him to even witness a bird in a cage, or see any animal not enjoying the freedom they were meant to enjoy.

Birds were a special source of pleasure to Bill, and in the rural area of the third relocation of the Miami Serpentarium to Punta Gorda, Florida in 1990, he was in an environment where birdlife was abundant and he took great pleasure in watching and interacting with them.

Bill and sandhill cranes

In later years, snake procurement became more difficult as the interest in keeping venomous reptiles for personal enjoyment in private collections became increasingly popular, and remains so today. This demand by the "pet" trade created competition for the animals needed for venom collection, as suppliers could charge elevated prices that hobbyists were willing to pay.

Breeding them in captivity was in some cases possible, but that is a slow, difficult process whereby if juvenile snakes were to be presented from an egg or born live, and how this happens is a subject for another time, and although they start life with venom and fangs and they know how to use them, they are very delicate and the time it would take to raise them to a size where they could produce any significant amount of venom would be long and impractical for most species.

That reality plus the recognition of the hardships that bringing animals who have evolved from different global environments to the sea level altitude or lack thereof, and high humidity and heat of Florida, were always factors in keeping delicate reptiles alive and which had to be accommodated for as much as possible. Many venomous snakes are found in tropical or sub-tropical regions of the world, but snakes from the desert or mountainous regions were affected the most, the elevation problem was one factor that was impossible to overcome.

So all in all, as part of the evolutionary process of the Miami Serpentarium, it became more practical and beneficial for the animals not to have them removed from their environments but to rely upon production stations around the world who could provide venoms according to our strict requirements. While venomous snakes were still procured, it split the burden of keeping them in large numbers, spared subjecting the reptiles to the rigors of shipping and adaptation, and accommodated the realities of changing times, including the stricter regulatory restrictions controlling their import which steadily increased.

Although wildlife regulating agencies are very effective in protecting wildlife worldwide and rightly so, they need to be mindful of the value of the venoms of snakes in medicine and science, and take into account the specialized needs of venom production companies in the formation of new wildlife laws. These specialized companies, whose service to mankind is essential to the health and well-being of people around the world, must be protected through exemptions or some other means if they are to be expected to continue to provide the life saving service of producing venoms for antivenin, scientific research and new drug development.